Portions of this article are excerpted and adapted from the upcoming book Hope Against Hope, authored by Renascent’s Clinical Director Michael Lochran and consulting Psychotherapist Laura Cavanagh. Hope Against Hope’s anticipated release is in 2022.

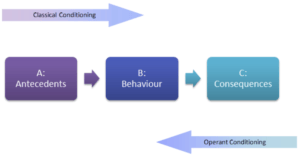

Is addiction a learning disorder? Behavioural psychology looks to the principles of learning to answer this question. Behavioural psychologists define behaviour objectively. Rather than guessing at what’s going on inside people’s heads, they prefer to look at what we can see, hear, and measure. They say that if you take away all the talk about what’s going on behind the scenes, behaviour boils down to a simple equation: something triggers a behaviour, it occurs, and it is followed by consequences (positive, negative, or neutral). Behaviourists call this the ABCs of behaviour: the triggers are called antecedents (A), our responses are the behaviours (B), and these behaviours result in consequences (C).

One of the most important behavioural processes is called operant conditioning. The basic principle of operant conditioning is that behaviours are followed by consequences, and these consequences determine whether or not a behaviour will be repeated. Operant conditioning relies on reinforcement and punishment. Reinforcement is any consequence that makes a behaviour more likely to be repeated. Punishment is any consequence that makes a behaviour less likely to be repeated.

Reinforcement

We often think of reinforcement as reward, but reinforcement is actually the process by which a stimulus strengthens (reinforces) the learning of a behaviour, making it more likely that a behaviour will be repeated. If a rat presses a lever and gets food, the behaviour of pressing a lever is reinforced by the provision of the food reinforcer (reward). This reinforcement means that the rat will be more likely to press the same lever in the future to get more food. The rat is learning to press the lever because of the reinforcement provided by the food. Many people use the terms reward and reinforcers interchangeably, but behavioural psychologists prefer the term reinforcer because it is more objective. The term reward implies subjective enjoyment, but a reinforcer is anything that strengthens a behaviour, making it more likely to be repeated.

Reinforcement has a biological basis for its effect on behaviour. Reinforcers cause a surge of dopaminergic activity in the brain. Primary reinforcers (food, sex) naturally increase dopamine activity in the mesolimbic dopamine system (MDS), which is the key area of the brain that is involved in addiction (see The Neurobiology of Addiction, Part Two ). But secondary reinforcers come to raise dopamine levels too. When we receive praise, or get our paychecks, or see “likes” coming in on our social media posts, a flood of dopamine is released within the MDS, resulting in reinforcing feelings of pleasure. This dopamine surge also activates the incentive system, which makes the behaviour more likely to be repeated.The more it is repeated, the more thoroughly it is learned.

Positive Reinforcement

You may have heard the terms positive and negative reinforcement before. Reinforcement is the process by which a consequence strengthens a behaviour, making it more likely to be repeated. Positive reinforcement occurs when a stimulus is added or provided as a consequence of a behaviour, thereby increasing the likelihood of the behaviour being repeated. Praise, money, food, or points are frequent examples of positive reinforcers. When a behaviour is positively reinforced, it is likely to occur more frequently. If a rat pushes a lever and gets food, it is likely to push the lever again because receiving food was positive reinforcement for the behaviour of pushing the lever. Getting paid is positive reinforcement for coming to work. Earning good grades positively reinforces the behaviour of studying.

Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement occurs when a stimulus is removed as a consequence of a behaviour. Negative reinforcement, like positive reinforcement, increases the likelihood that a behaviour will be repeated. Positive and negative reinforcement are both experienced as pleasant or desirable consequences.

Suppose you have a headache. The headache is an unpleasant stimulus. When you take a painkiller, the headache goes away. The behaviour of taking a painkiller is negatively reinforced by the headache being relieved. When you get a headache next time, you are likely to take a painkiller again, because taking the painkiller was negatively reinforced last time.

Negative reinforcement has a very powerful effect on behaviour. In fact, negative reinforcement is a more powerful learning process than positive reinforcement, because we are more motivated to relieve discomfort than to gain reward. Pressing snooze, for instance, is reinforcing because the sound of the alarm stops – an example of negative reinforcement. The behaviour has been so powerfully reinforced that many of us can literally press the button in our sleep!

Punishment

Reinforcement is any consequence that makes a behaviour more likely to be repeated. Punishment, as the term is used in operant conditioning theory, is any consequence that weakens a behaviour, making it less likely to be repeated. If a rat presses a lever and gets food, it will press the lever again because it was reinforced by the arrival of food. If a rat presses a lever and gets an electric shock, it is unlikely to press that same lever again. Pressing the lever was punished by the electric shock.

We often think of punishments as consequences that are imposed, like fines, time-outs, electric shocks, or sanctions. But in operant conditioning terms, punishment is anything that makes a behaviour less likely to be repeated. These can include natural consequences: consequences that occur inevitably because of the behaviour. If you stay up until 3 a.m., being tired is a natural consequence that – because it is unpleasant – is a punishment. Forgetting your gloves has a natural consequence that is punitive: cold hands.

Like reinforcement, what constitutes punishment depends on the individual. Getting sent home early from your shift for being late could be a punishment if you were hoping for more money, but it could be a reinforcer if you were hoping for more free time. How do we know if something is a punishment for a particular individual? Punishment – like reinforcement – is defined by its effect on behaviour. If a behaviour is decreasing in frequency, it is being punished. If it is maintaining or increasing, then – somehow, somewhere – it is being reinforced.

Punishment can produce very rapid behavioural change. Natural consequences in particular can be very effective in motivating someone to change their behaviour. If you forget your bank card and can’t buy yourself coffee or lunch at work you are very likely to remember your bank card going forward. However, imposed punishments – aside from being ethically problematic in many cases – are rarely effective in producing long-lasting behavioural change. Think of a speeding ticket: it may lead you to slow down and watch out on the stretch of highway where you got the ticket, but it is unlikely to cause a habitual speeder to regularly begin driving the speed limit.

In addition, imposed consequences (as opposed to natural consequences) often have unpredictable effects on behaviour. A school may dole out a suspension intended as a punishment, but it may not have the desired effect if a student does not want to remain in school. Interestingly, a 2000 study looked at the effect on parents’ behaviour when daycares introduced fines for late pickups. Behavioural economists wondered whether introducing fines for late pickups would encourage parents to arrive on time to collect their children at the end of the day. Half of the daycares in the study introduced financial penalties for late pickups, while the other half did not. The researchers found that in the daycares where fines were introduced, late pickups increased significantly – in fact they doubled! Not only that, but the average amount of time by which parents were late increased after the fine was introduced. The daycares that did not introduce a fine experienced no change in the number of late pickups (Gneezy & Rustichini, 2000). The financial penalties were intended as punishment. But in operant conditioning terms, punishment is defined by its effect on behaviour. A stimulus is a punishment if it leads to a decrease in behaviour. In this case, the behaviour did not decrease at all, but rather increased, meaning that it was somehow being reinforced. How is this possible?

It turned out that, for the parents, what was actually punitive about turning up late was the guilt they felt about facing the teacher who had stayed late to watch their child. Once the fine was introduced and they could pay for their time, that punitive consequence (feeling guilty, feeling embarrassed, having to apologize) was eliminated. Whatever was reinforcing about being late – perhaps having a few more minutes to wrap up at work, or being able to drive at a more leisurely pace, or being able to pick up dinner on the way – now outweighed the punishment of the fine. Previously, the punishment of the guilty feelings outweighed these potential reinforcers, enough to keep tardiness at a relatively low baseline level. Once the fine was introduced, and the punishment of feeling guilty was effectively removed, the pull of these reinforcers outweighed the punishment of the fine.

Operant Conditioning Processes in Addiction

What does this mean for addiction? As we saw in the example above, a behaviour may be both reinforced and punished simultaneously. This is certainly true in addiction.

Positive Reinforcement and Addiction

Many people assume that positive reinforcement plays a primary role in alcohol and substance addiction. In fact, we once assumed that the addictive liability of drugs had to do with the quality of the high – the better the high, the more addictive the drug. We now know from neurobiological research that all addictive substances and processes cause a surge of dopaminergic activity in the brain’s incentive/reward circuit, the mesolimbic dopamine system (MDS). This is experienced as subjective feelings of pleasure, and the behaviour of using is reinforced. Reinforcement strengthens the behaviour, making it more likely to be repeated. What any one individual finds reinforcing about the intoxicative experience may vary – some may enjoy feeling uninhibited or confident, others feeling relaxed or “high” , while still others feel creative or an altered state of consciousness. Substance use may be accompanied by other positively reinforcing experiences: inclusion in a social group, feelings of interpersonal connectedness, or other positive experiences.

As this is occurring, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is engaging in its salience attribution responsibilities (see the Neurobiology of Addiction Part One). The artificially strong surges of dopaminergic activity caused by the drug result in the substance itself and its associated stimuli being assigned disproportional incentive and emotional salience. The OFC assigns incentive salience based on the sheer strength of the dopamine response. The incentive salience of the substance comes to outweigh that of any other needs. The false need for the drug is weighted above others, and its perceived reward is valued more.

The distortion of positive reinforcement processes in addiction is particularly harmful. Not only does the brain raise the incentive salience of the drug, it knocks down the salience of other rewards. The 2015 documentary Amy, a film about the late musician Amy Winehouse, captures her rise to fame and her dramatic fall into addiction. Winehouse is shown at the 2008 Grammy Awards during a brief period of sobriety. She performs two of her critically-acclaimed hits, including Rehab, a song describing her refusal to seek treatment for substance use disorder. Her art and talents are celebrated and praised. She wins five awards, including Song of the Year for Rehab. She then turns to a friend and says: “Jules, this is so boring without drugs” (Kapadia, 2015).

Amy’s pleasure circuits had been disrupted by substance misuse, such that it was impossible for her to experience pleasure from other rewards, even on this once-in-a-lifetime night. This state is known as anhedonia, and it is characteristic of the withdrawal stages. It’s common in clinical practice to hear our clients say that they cannot imagine enjoying sex, food, travel or other experiences without their drug of choice. Engaging in these activities feels pointless if they are not also paired with substance use. This is a result of distorted incentive salience: it feels like these activities are only pleasurable when they are experienced in conjunction with using.

The brain must heal from the disruptions to the dopamine system to be able experience positive reinforcement from other stimuli, and this re-calibration takes time. The addicted individual must trust in the long-term potential for reward from their choices as earlier damage make it difficult or impossible to experience pleasure in the early stages of recovery.

Negative Reinforcement and Addiction

The positive reinforcement of substance use stems from its pleasurable effects of feeling high. These effects have a ceiling however. And, in fact, the pleasure experienced from consumption of a substance or engagement in a behaviour decreases dramatically with time. Studies show that drug use does not decline even when the drug’s intoxicating effect is largely blocked (Haney, 2008; Haney et al., 1998; Haney et al., 1999). In clinical practice, many individuals will tell us that they have been, for years, seeking a high that they have not experienced since early in their use history.

But another process also accounts for this persistence: negative reinforcement. Recall that negative reinforcement occurs when a behaviour is strengthened as a consequence of the removal of an unpleasant stimulus. Negative reinforcement has an extraordinarily powerful effect on behaviour, even more so than positive reinforcement. We are far more motivated to alleviate discomfort than to seek reward.

Hedonic Deficit and Withdrawal

Positive reinforcers (belonging, pleasure) may come first in the early stages of substance use, but negative reinforcement processes maintain and increase rates of substance misuse over time. From a biological perspective, repeated use of a drug causes the rebound effect within the brain. For all addictive substances, the brain adjusts by producing less and less dopamine. This “dopamine deficit” means that the user has chronic feelings of sadness, discomfort, and dysphoria. To alleviate the dopamine deficit, the user increases dosage and frequency of use. This is not to experience pleasure but just to “get back to zero” or to “feel normal” now that the user is operating at a deficit. This results in a further decrease in natural dopamine production and a desensitization of the dopamine system. The individual must consume more and more to get back to zero. The cycle of consumption is no longer about experiencing pleasure (positive reinforcement) but about alleviating the feelings of sadness and inability to feel pleasure that actually stem from the drug use itself. This creates a cycle of negative reinforcement which becomes increasingly difficult for the user to break (Ahmed, Kenny, Koob, & Markou, 2002; Ahmed & Koob, 2005).

Self-Medication and Self-Harm

Negative reinforcement drives substance use in other ways. Substance use offers a means of alleviating uncomfortable thoughts, feelings, memories, and emotions – creating a cycle of negative reinforcement.

For example, someone may drink to alleviate the symptoms of anxiety. The temporary relief from the symptoms is negatively reinforcing, thereby increasing the likelihood that the individual will drink again. This is a self-medication model that may work for the individual for a period of time. As tolerance builds and the pleasurable effects of alcohol level off, the effect will wear off, and the person will either need to consume more or stronger substances to get the same relief.

The cycle of self-harm is further accelerated because the substances themselves create the symptoms that the individual is seeking to relieve (Brinson & Treanor, 1984/2005; Childs, O’Connor, & DeWit, 2011). We refer to this as the self-medication paradox. For example, the withdrawal effects from alcohol include agitation and anxiety. Increased anxiety and insomnia are experienced as rebound effects from cannabis use. Pain is a rebound symptom caused by misuse of the painkilling opioids. The use of the drug itself worsens the symptoms over time, leading to a more rapid cycle of negative reinforcement. The increase in the troubling symptoms from the use of the drug leads to states of discomfort that are more intense than the original state that the user was trying to relieve. The individual’s desire to seek negative reinforcement is heightened. The more the individual uses the drug to alleviate its own symptoms, the more the behaviour is strengthened.

The cycle of negative reinforcement is very difficult to break. Negative reinforcement has a powerful effect on behaviour. We are highly motivated to alleviate discomfort (stress, pain, sadness) – far more so than we are to gain reward. In addition, the quick effect from a reinforcer partly determines its effect on behaviour. In the negative reinforcement cycle, relief is experienced immediately, whereas the rewards of cutting down or cessation are often delayed.

Punishment and Addiction

Punishment is any consequence that decreases the likelihood of a behaviour recurring. In operant conditioning terms, punishment competes with reinforcement, which increases the likelihood of a behaviour being repeated. Punishment is often relied on as a motivational factor for people with addictions. It is assumed that once the punishments start to outweigh the reinforcing consequences, individuals will stop using or be willing to seek treatment if they cannot stop on their own. This has led to the notion of the “rock bottom” in popular culture, which states that an individual must reach a certain low in terms of adverse consequences before they will have the motivation to quit. Although many individuals identify with this concept, it has very limited utility. Persistence in the face of consequences is a defining feature of addiction, and occurs because of the strength of negative reinforcement processes and because the malfunctioning OFC leads to distortions in incentive salience. And, in fact, addiction becomes more difficult to treat further along in its progression, even though the consequences by that point are far more serious

Certainly, for some individuals, adverse consequences do provide motivation to decrease substance use or to seek recovery. Many individuals describe a wake-up call from consequences like an impaired driving charge or disciplinary action at work. In these cases, it seems like the consequence pierces the denial associated with substance use disorders.

But adverse consequences can have unpredictable effects in addiction. The pain of the adverse consequences experienced, or the shame triggered by what has occurred while active in the disease, can create a state of mental tension. This might push the individual to seek relief in a continued cycle of negative reinforcement.

We know that earlier intervention is more effective than intervention later in the progression of the disease, despite the fact that the consequences incurred later are more severe. This indicates that the “rock bottom” concept has less clinical utility than we might have believed. The punishing effects of adverse consequences are often outweighed – in terms of their effect on behaviour – by the negative reinforcement cycle that they fuel. As consequences become increasingly severe, so does the desire to escape the pain.

Behaviourists have recognized for years the limitations of punishment in motivating and sustaining long-term behavioural change. Clinicians, loved ones, and society as a whole are urged to move beyond the rock bottom idea to get people to make a change. If you or a loved one needs help, the time to seek it is now. The more consequences pile up, the harder the addiction is to treat.

The Renascent Difference

Our clinicians are trained in analyzing the processes of learning and behaviour. They are able to help clients’ recognize how these processes are affecting their own behaviours, because when we understand our behaviour we can take strides to change it. Our counsellors have lived experience as well as learned experience, making them uniquely able to empathize with the anhedonia period in acute and post-acute withdrawal – but also to serve as an example that this state will pass. Our clinicians have moved beyond reliance on the “rock bottom” notion, and use other tools, including motivational interviewing, to help our clients build the readiness and motivation to seek sustained recovery.

With the recognition that negative reinforcement plays a particularly powerful role in maintaining substance use, we have trained our counsellors in Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT). This evidence-based therapy is specifically designed to address the negative reinforcement processes that entrench addiction.

Renascent Can Help

At Renascent, we are committed to an evidence-based approach that follows the science and the research. Our counsellors come in with lived and learned experience in addictions, and we are committed to their ongoing professional development so that we can always ensure our clients are receiving best practice in treatment.

Contact us today to find out how Renascent can help. Recovery is possible.

Selected References

Ahmed, S. H., Kenny, P. J., Koob, G. F., & Markou, A. (2002). Neurobiological evidence for hedonic allostasis associated with escalating cocaine use. Nature Neuroscience, 5(7), 625–626. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn872

Ahmed, S. H., & Koob, G. F. (2005). Transition to drug addiction: a negative reinforcement model based on an allostatic decrease in reward function. Psychopharmacology, 180(3), 473-490. 10.1007/s00213-005-2180-z

Gneezy, U., & Rustinchini, A. (2000). A fine is a price. The Journal of Legal Studies, 29(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1086/468061

Haney M. (2009). Self-administration of cocaine, cannabis and heroin in the human laboratory: benefits and pitfalls. Addiction biology, 14(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00121.x

Haney, M., Collins, E. D., Ward, A. S., Foltin, R. W., & Fischman, M. W. (1999). Effect of a selective dopamine D1 agonist (ABT-431) on smoked cocaine self-administration in humans. Psychopharmacology, 143(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002130050925

Haney, M., Foltin, R.W., & Fischman, M. W. (1998). Effects of pergolide on intravenous cocaine self-administration in men and women. Psychopharmacology, 137, 15–24

Kapadia, A. (Director). (2015). Amy [Film]. Globe Productions. Full transcript available at: https://www.tvo.org/transcript/405787X/amy

Read Less…