This article is the second in a two-part medical series explaining the underlying biology and brain science of addiction. Portions of this series are excerpted and adapted from the upcoming book Hope Against Hope, authored by Renascent’s Clinical Director, Michael Lochran and consulting Psychotherapist, Laura Cavanagh. Hope Against Hope’s anticipated release is in 2022.

Addiction is a chronic, relapsing, but treatable disease of the brain. The neurological basis of addiction accounts for the painful and often puzzling behaviours of addiction.

The disease of addiction is defined by an overpowering desire and compulsion to consume a substance or engage in a troubling behaviour, even in the face of negative consequences.

In our first article in this series, we reviewed the neurobiological foundations of craving and discussed how neuroscience explains the persistence of use even as negative consequences accumulate in a person’s life.

Neuroscience can also help us to understand one of the most heart-breaking symptoms of addiction: relapse.

More importantly, lessons from neuroscience can help us to avoid it too.

Neuroscience, Addiction, and Craving

Different substances affect different chemicals in our brains. Opioids are near-clones of our own natural pain-killing endorphin hormones. Cannabis affects the endocannabinoid system. Cocaine and amphetamines (including crystal meth) stimulate the dopamine system directly. Ketamine, GHB, and other dissociative anesthetics inhibit the glutaminergic system. Alcohol and the benzodiazepines affect the GABA system. Hallucinogens like ecstasy and acid have their effects on serotonin.

It may surprise you, then, to learn that common brain areas are involved in ALL substance addictions, regardless of the drug. And these same brain areas are involved in behavioural addictions too.

Doctors call this the mesolimbic dopamine system or MDS, and it is the key area of the brain affected in addiction, regardless of a person’s drug of choice. All drugs—whether they have a direct action on our dopamine system or not—raise the activity within the MDS. This critical circuitry in our brain is involved in regulating reward and motivation. For example, activation of the MDS causes feelings of pleasure but also of craving. The dual incentive/reward function leads to the overvaluing of the pleasure potential of the drug, and also to the defining feature of addiction: craving for more.

Addiction is not about the chemical action of any given drug. Rather, the neurocircuitry of addiction—regardless of drug of choice or behavioural addiction—lies within the MDS.

And, all drugs and behavioural addictions, whether or not they have a direct effect on dopamine, raise dopamine levels within the brain. Ongoing blasts of dopamine cause injury and malfunction to the MDS, which is the neurological footprint of addiction.

Cravings and Relapse

Cravings are normal experiences within addiction recovery. Cues associated with drinking or drug use can trigger intense experiences of craving. Associated cues are any environmental stimuli (people, places, events, experiences, or things) that are linked with the consumption of a drug or behaviour of concern. These associated cues have significant emotional and behavioural impacts on people with addictions.

Because activation of the dopamine system within the brain does not actually depend on any chemical component of the drug, the reward experience of addiction actually begins before the drug is consumed. Increased activity is seen within the dopamine system when a person with an addiction is exposed to cues associated with drug use. The euphoric rush begins just from the thought that the drug could be used.

In our clinical and treatment practice, this fits with firsthand accounts. People with substance use or addictive disorders will speak of the rush of pleasure from prepping for IV injection, or uncorking a bottle of wine, or walking into a casino.

Raised activity levels within the MDS turn on the reward experience, but also the desire experience. Many individuals relapse after inpatient addiction treatment in a treatment centre when they are exposed to the environmental stimuli (“people, places, and things”) associated with their substance use or addictive behaviour.

The potential for associated cues and even thoughts or memories to induce craving by activating the dopamine system continues long after the physical dependence has passed. Persistent activation within these areas can lead to relapse.

Why is Relapse Cause for Concern?

Relapse is important to consider in the disease of addiction because of its often-catastrophic consequences.

If a person in recovery from alcohol use drinks a single beer, that would hardly be a reason to worry. However, addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing condition because of the fact that relapse often predicts a reinstatement of use. This means that relapse often leads to a return to the alcohol or drug-seeking and using behaviours that the person displayed in the more advanced stages of their disease.

Reinstatement may occur quickly or gradually, but it typically involves a much faster progression than the original presentation of addiction. When we consider this from a neurobiological perspective, this can be accounted for by the enduring neurocircuitry of addiction or the feedback loop—after relapse, addiction circuitry does not need to be built but simply reactivated and strengthened.

What Predicts Relapse?

Stress is one predictor of relapse, but the most reliable predictor of a return to the negative patterns of alcohol and drug consumption in addiction is exposure to the substance itself.

In fact, scientific animal studies show that a single exposure to a drug leads to a reinstatement of compulsive drug-seeking and drug-using behaviour. Exposure to the substance raises activity level in the MDS. Remember that this system is both reward and incentive, meaning that it turns on that key feature of addiction—the craving for more.

The craving and desire triggered by that first exposure explains the well-documented phenomenon that relapse tends to lead to a rapid reinstatement of previous levels of use and even an acceleration of progression of use. Research supports what doctors and clinicians report: that a return to drinking or drugs leads to a rapid reactivation of the disease of addiction, even after an extended period of recovery. It is not a replay of the first-time progression of the disease, but a return to the more advanced stages.

This neurological sensitization also explains why people relapse even after long periods of sobriety: the neurocircuitry remains and can be reactivated by stress, cues, or exposure to the drug. When the MDS is activated, the phenomenon of craving is experienced, despite a lack of physiological dependence.

This gives us insight into what is, for family and friends, a frustrating and heartbreaking reality: that people relapse even when they are no longer physically dependent on the drug.

When we think about addiction as a chemical dependence, this is puzzling and, for loved ones, hurtful and infuriating. But when we understand that addiction is a brain disease, and not just a physical one, it makes a lot more sense.

I Was an Alcoholic, so it’s Safe for Me to Smoke Weed Right?

(Or, As Long As I Stay Away From Heroin, Can I Still Drink?)

Actually, no to both questions, because addiction lies in the dopamine reactions within the brain, not in the chemical properties of the drug itself.

The fact that the dopamine-related effects of addictive drugs and behaviour are universal for all people accounts for a perplexing phenomenon: that reinstatement of drug-seeking and drug-using behaviour occurs when people relapse on substances to which they were never addicted in the first place!

If you are experiencing this, you are not alone. But also know it is so important to get help. There are many well-known people in popular and celebrity culture who have openly shared their struggles with relapse, and unfortunately, not all of them got the help they needed. Duff McKagan, bassist of the rock band Guns ‘n’ Roses, relapsed on benzodiazepines (Xanax) after a period of sobriety. His drugs of choice were cocaine and alcohol. According to his book, he got clean again after his relapse and has been sober since 2005. Similarly, actor and podcast host Dax Shepard shared publicly how he relapsed on opioids after 16 years of sobriety. His original substances of choice were alcohol and cocaine, but he became addicted to prescription drugs. Following an extended period of opioid misuse, he has been clean since September 2020.

Chester Bennington, lead singer of Linkin Park, got clean from hard drugs and had an extended period of sobriety, but relapsed on alcohol. Sadly, Bennington took his own life in 2017. Scott Weiland, singer from Stone Temple Pilots and Velvet Revolver, fought addiction for years; he was a poly-drug addict whose primary drug of choice was heroin. According to his book, he got clean from heroin but tragically relapsed on “a single line of coke”. He died of the disease of addiction a few years into this relapse. . Dopey Podcast co-host Chris (who kept his last name anonymous in the tradition of 12-step programs) had nearly five years sober from alcohol, cocaine and heroin. In 2018, he relapsed on painkillers and died of a fentanyl overdose. He was working on his PhD in Clinical Psychology at the time of his death.

These stories highlight that addiction is a serious disease that has many ways to hurt, even kill. It’s not about the drug of choice, but about the underlying neurobiological disease: Addiction.

Remember, all addictive drugs—whether legal (alcohol, cannabis), prescription (Xanax, oxycodone), or illegal (heroin, cocaine)—cause a dopamine reaction in the brain. It is the powerful dopamine rush, rather than the specific action of the drug (heroin on the endorphin system, alcohol on the GABA system, and so on) that triggers the reactivation of the neurocircuitry, the feedback loop, of the disease. This explains why reinstatement of drug use behaviours can occur regardless of whether or not a person’s history of use is with that particular drug.

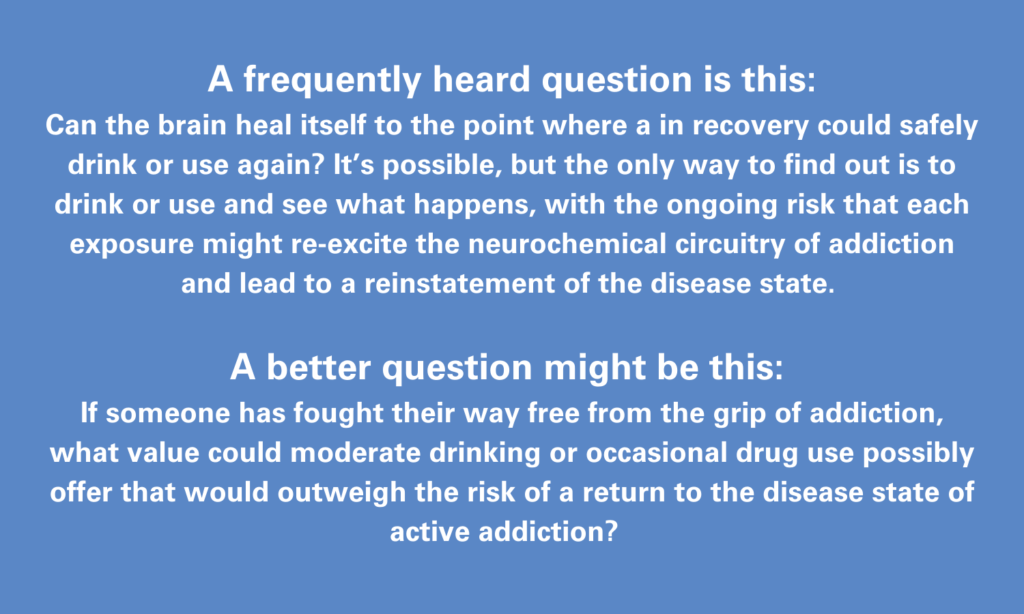

Could there come a point where a person’s MDS has healed to the point where they could use in moderation without triggering a reactivation of the disease? It’s certainly possible. Scientific studies show significant (though not full) recovery within the dopamine system after one year to 17 months of abstaining from use, even among meth users, whose dopamine system sustained significant injury from meth’s dramatic neurotoxic effects.

There is no reason to think that the MDS does not continue to recover and heal past this point. The problem is that there is no way to tell whether the MDS has recalibrated other than by exposing yourself to the drug and seeing what happens. And even if first exposure does not trigger behavioural reinstatement, it is possible that continued exposure to the drug might re-excite the neurochemical circuitry and lead to relapse.

A better question might be this: if someone has wrestled their life back from the grasp of addiction, what value could, say, moderate drinking or occasional cannabis use offer that would outweigh the potential risk of a return to the disease state of addiction?

Why Choose Renascent?

Renascent is committed to evidence-informed best practice. This means we follow the best science.

Whether this is your first addiction treatment experience or your tenth, we know that recovery is possible. Relapse is a symptom of the chronic disease of addiction. Chronic diseases are not cured; they are either active or in remission. Relapse is not a moral failing, and it’s not a choice: it’s a recurring episode of a poorly treated chronic disease.

Recovery is possible for everyone, and at Renascent we know that a critical part of sustained recovery is learning how to keep a chronic disease in remission. We equip our clients with the tools to keep their disease in remission and to avoid the risks of relapse going forward—no matter how many times they have relapsed before.

At Renascent we follow an abstinence-based recovery model because we follow the best science. We teach our clients about the nature of addiction and we give them the tools to recover. Recovery is not about finding a way to safely use drugs or drink, but about finding a way to build a life where you no longer turn to drugs or alcohol. We know that this is possible; we’ve seen it happen for so many of our successful graduates for more than 50 years.

When you choose Renascent—whether for yourself, your loved one, your employee, family member or friend—you are choosing a program that is not just about the days in treatment but all the days that come after treatment that, strung together, build a lifetime of recovery.

Your road to recovery starts here.

Talk to someone who’s been where you are. Get help today.

Related Reading

The Neurobiology of Addiction – Part One: The Importance of Alcohol- and Drug-Free Recovery